Introduction Link to heading

What are type parameters? Type parameters are just variables, plain and simple. It is no coincidence that they are referred to as type variables as well.

Variables…really? Link to heading

Yes! Let’s take the following function definition as an example:

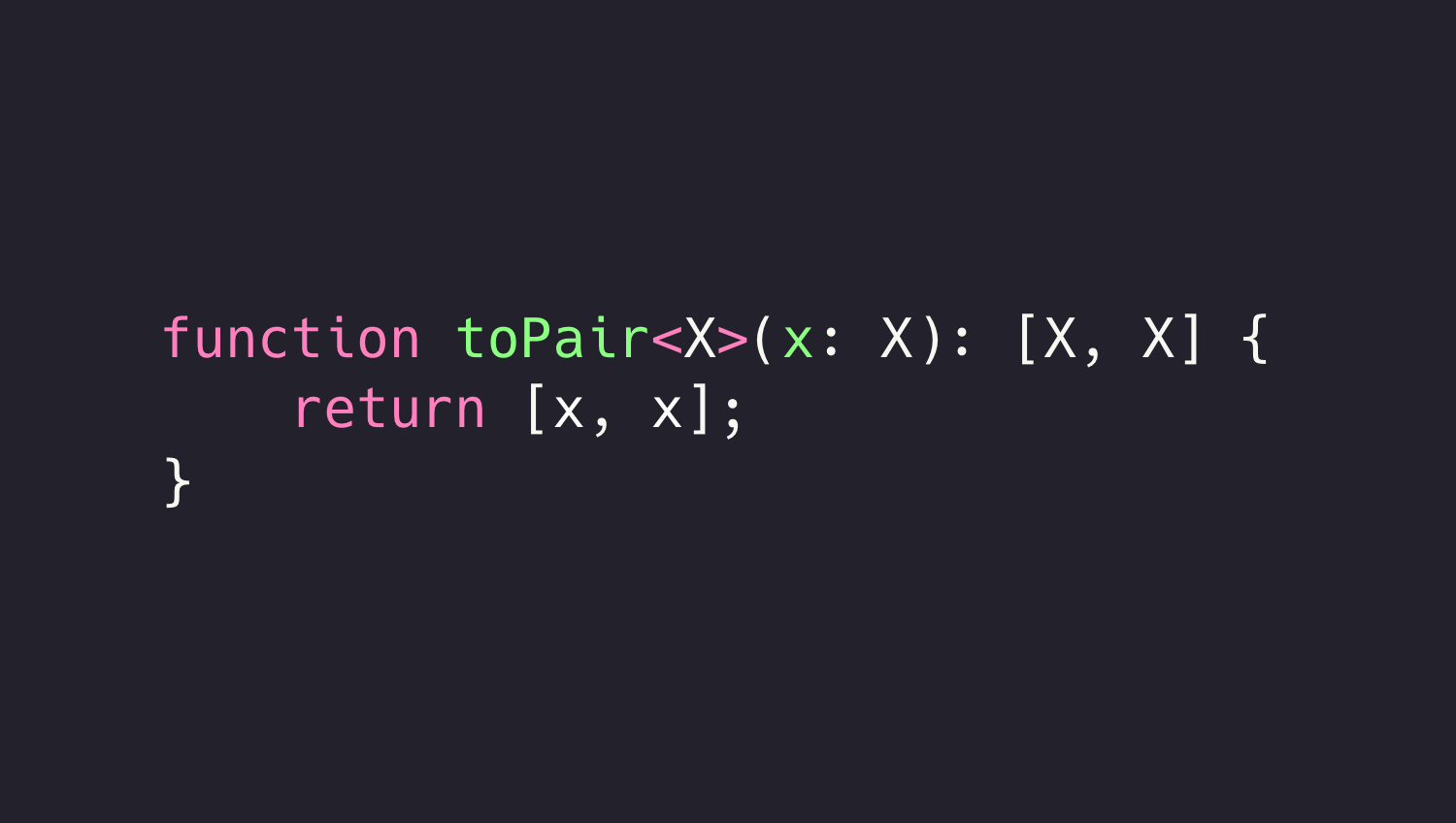

function toPair<X>(x: X): [X, X] {

return [x, x];

}

We may be used to seeing toPair as a generic function that, given any x of some type X, duplicates it, producing the pair [x, x] of type [X, X]. However, this way of looking at things hides, from my point of view, the true nature of type parameters.

We can be a little more precise: the toPair function declares an input type variable X, effectively taking a type as input, and returns a function that, in turn, takes any x of type X and duplicates it, producing the pair [x, x] of type [X, X].

From a formal point of view, toPair is a slightly bizarre function because it takes a type as input but returns a term, that is, a value that actually exists at runtime (the function that duplicates x). How can we invoke toPair? With angle brackets <>:

const toPairNumber = toPair<number>

// toPairNumber: (x: number) => [number, number]

const toPairString = toPair<string>

// toPairString: (x: string) => [string, string]

The first time we invoke toPair with the type number, we get a function that takes a variable x of type number and returns a pair of numbers. In this case, the type variable X will be equal to number. The second time we invoke toPair with the type string, we get a function that takes a variable x of type string and returns a pair of strings. In this case, the type variable X will be equal to string.

We can see that the type variable X behaves exactly like a variable: in the first case, X will have the value number, and in the second case, X will have the value string. As unintuitive as this may sound, there is nothing special about it. The compiler, which has internal representations for the number and string types, also has the ability to represent type variables with appropriate data structures. It can associate these variables with concrete types, as in the example above, and with other type variables in certain circumstances.

The compiled code Link to heading

Since TypeScript does not exist at runtime and the engines that run JavaScript code do not exploit type annotations in any way, the above code will be compiled into something like this:

function toPair(x) {

return [x, x]

}

const toPairNumber = toPair

const toPairString = toPair

It’s worth noting that the generated JavaScript code contains no trace of the type variable X and that the toPairNumber and toPairString functions are actually the same toPair function with a different name. Considering toPair a function from types to terms (values) is just an abstraction, the same one used by System F to describe the behavior of polymorphic functions, although behind the scenes, in JavaScript, it is just a trivial function from terms to terms.

Other programming languages may not work this way: for example, in Rust, different input types could lead to the generation and invocation of different functions because the size of the activation record of each function must be known in advance. The existence of terms that depend on types is more evident in such cases.

What about type inference? Link to heading

TypeScript is able to infer the type of a type variable based on the type of the argument passed to the function. For example, the following snippet:

toPair<number>(42) // [42, 42]

which encloses in a single line both the invocation of toPair with the type number and the invocation of the resulting function with the value 42, can be rewritten more concisely as:

toPair(42) // [42, 42]

since the compiler is able to infer that X is equal to the type number because 42 is of type number.

Unfortunately, inference somewhat obscures the nature of toPair and the necessary association between the type variable X and the concrete type number, an association that is implicitly performed by the compiler. Inference is a double-edged sword when trying to understand these concepts: on the one hand, it allows us to write more concise code, but on the other hand, it makes us lose sight of the elements at play since the compiler takes care of everything.

When to use type parameters Link to heading

Every time you need to keep track, in the type system, of a type that is not known in advance. Type variables are variables, and TypeScript uses them to store types, but if we don’t use them later, then there is no point in having them instantiated. I believe that knowing when not to use generics is the best way to learn how to use them effectively. More on this in a future article.